Bechdel's Tiers

One of the things that I’ve already noticed about this project is how much it has impacted not only the way I’ve been reading comics, but also the way that I’ve been teaching them. This afternoon my undergraduate class wraps up its study of Alison Bechdel’s memoir Fun Home, one of the most remarkable (and most studied!) comics of the past decade.

When we discussed this book in our last meeting, there was a pretty clear consensus in the class that pages 220 and 221 were the “most important” pages in the book. Certainly that is easy to see both narratively (it is Alison’s last important conversation with her father), thematically (it is the scene in which the facts are laid bare), and even formally. What is striking here is the use of the four-tiered grid, the regularity of the panel sizes, and the density of the panels, all of which seem unusual given the previous 219 pages of the book.

Throughout Fun Home, Bechdel uses a small number of single tiered pages (splash pages) as chapter titles:

Most of the book relies on pages with two or three tiers, with the three tier page predominating:

The counting of these tiers will be one of our most important undertakings in this project. In our shorthand while talking about this project we’ve often said we’re counting pages, then panels per page, then balloons per panel, then words per balloon. That’s crude and inaccurate, but it at least gave a general sense of the first stage of our project. Yet even the most cursory glance at a comic book page will demonstrate that before the panel comes the tier - it is central to the geography of the comics page. Moreover, it is not simple. The pages above are all relatively uncontroversial in terms of tier count. But what about this one?

When that first panel stretches over two tiers, do we count this as three? I think that most critics would say that we should, that this page has three tiers but that one panel happens to be in two of them. That’s more of a coding issue than an analytic one.

But what about this?:

If the previous page was three tiers, this is clearly four. Yet there is something about this page that makes it seem like three - probably the fact that only one of the first two panels has a caption, which makes the lower one seem like it could be part of the upper one. Regardless, I think that this has to be counted as four tiers. That would make this the first four tier page in the book. It also makes the conversation in the car slightly less formally anomalous. Similarly, this page probably needs to be counted as having four tiers:

One of the interesting things about Fun Home is that once Bechdel introduces the four-tiered page, she begins to use it more frequently. I think that an argument could be made about this page being either four or five-tiered:

Nonetheless, it is this conversation between Alison and Bruce that most leaps out at us. Perhaps not because of the number of tiers, but because of the regularity of the panel sizes and the density. There are no other pages that have anywhere near to the number of panels that Bechdel uses here.

After the conversation, which comes extremely late in the book, the four-tiered page becomes a semi-regular feature:

Given the importance of this scene, I think that any analysis that doesn’t take into consideration the increasing importance of the tier as a unit of page design is likely going to be on shaky ground.

Bechdel’s book also poses some interesting conundrums for our coding (if it is randomly selected as part of our sample), but probably not much more than many others. I think that some people presume that the count of panels, for instance, will be relatively straightforward, while the coding of panel transitions (a la Scott McCloud) will be more interpretive. That is certainly true, but panels themselves can cause problems. Bechdel frequently uses panels without images, just text:

To my mind there is no doubt that the panel beginning “It could have been” is, indeed, a panel. Yet what about the other text. What about “He would cultivate”. Bechdel’s captions are overwhelmingly in the gutters in Fun Home (interestingly, this is a technique that she does not much use in her follow-up, Are You My Mother?). They seem intuitively connected to the images below them in a way that “It could have been” does not seem connected to the drawing of Alison watching It’s A Wonderful Life. Yet if the text had appeared above that image, and the image were stretched page-width, we probably would count this as a five panel page rather than a six panel page. There is something about the tier that determines the panel.

Let’s look again:

This seems to be a three-tiered page, with one panel made up entirely of text. Why is it, then, that “Wearing a black velvet dress” seems to not be a panel, while the text beside it does? Is it simply the presence of the panel border?

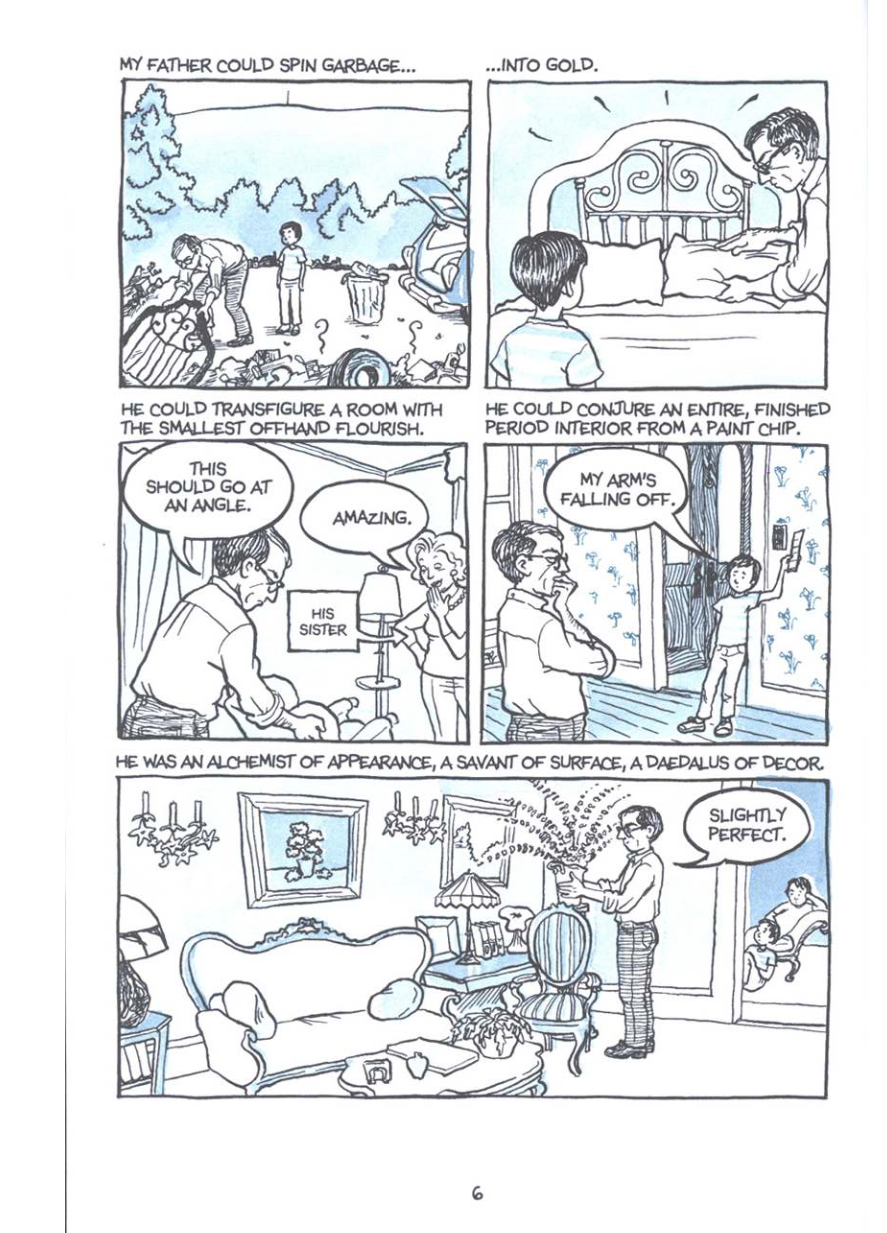

Finally, there are examples like the first tier here:

That caption spread across the two panels becomes not so much an analytic issue as a coding one (it is akin to a voice-over in film that stretches over multiple shots). This is a common comics technique (though not common in Fun Home). It is expertly deployed here - that is a terrific composition. But it is the type of thing that will begin to give our databases fits. There’s a lot to work on for such a seemingly commonplace rhetorical trope.

One thing that leaps out at me now as I look at comics is just much they lack standardization. When I mentally picture an Archie comic of the 1960s, for instance, I think of a three tiered page - but I know that there are so many pages that stray from that patterning. I think that by paying strict attention to the geography of the page as it changes over time or even within individual works we are going to learn a great deal.