Perpetually Falling Horse

Or, Lost in the Jungle.

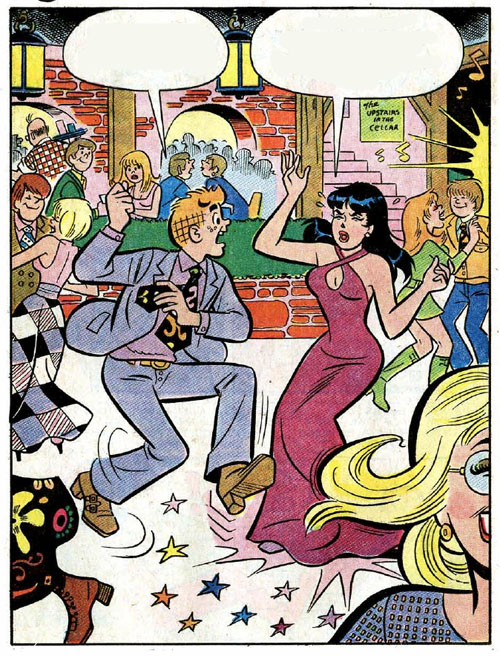

This morning I spent some time on the Digital Comics Museum looking at comic books from the 1930s and 1940s that are now in the public domain in advance of thinking through some of our coding protocols. Looking specifically at Jungle Comics 38 (Fiction House, 1943) I came across this page that initially flummoxed me. Here's the page:

You can imagine the story: the man is Kaanga, the blond king of the jungle, and here he is rescuing a woman named Julie who has foolishly tried to ride across a river just upstream from a waterfall.

What is unusual here is the second panel, which stretches across two tiers. Double-height panels are not at all uncommon in comic books of this period, but they seem less likely to appear in the middle of three columns than either side (something, I suppose that we'll have to verify empirically). Anyway, my initial presumption was that the page read in this direction:

Confronted with the tall panel in the middle, I assumed that the first move was to go down, then across. Yet if you read the captions, it is clear that this is not the case at all. The reading order is actually like this:

This reading pattern was surprising to me because of the long diagonal move back to the beginning of the second tier that moves through panel two again. Further, it is clear that the reader seems meant to skip the waterfall panel on the second left-to-right read through, otherwise that horse is simply hanging in midair forever. I suppose that might be one explanation for why Kaanga and Julie don't land on the dead horse at the bottom...

I'm not sure, precisely, how we would be meant to read this in terms of the typology that Scott McCloud provides in Understanding Comics. If we are not intended to re-read the waterfall, then the panel itself becomes a sort of over-sized gutter in an action-to-action transition. But that seems completely erroneous. Indeed, it seems that we are meant to go through the waterfall a second time - though maybe without the horse falling on us.

It's a dangerous business.